By Vice President of the Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security.

Originally published by the JISS 26.7.20

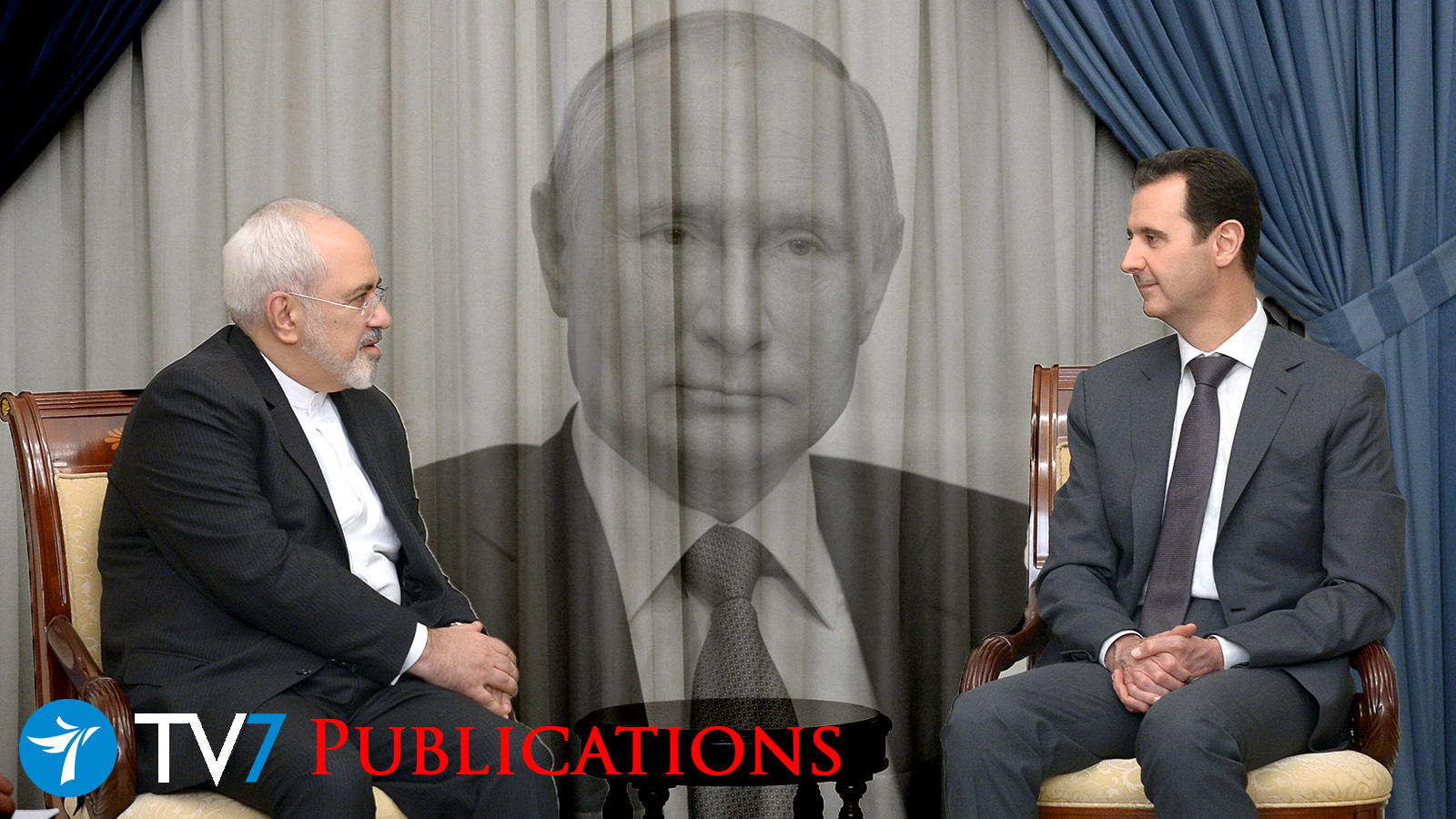

Israel and the US may have an opportunity to incentivize Assad and Putin to cooperate in constraining Iran’s presence in Syria.

Despite the recent military agreement between Syria and Iran, tensions are rising between the Assad regime and the Iranian ayatollahs. There is a rift within the ruling Assad family that weakens Iran’s influence in Damascus. More broadly, Assad’s cost/benefit analysis of Iran’s role is shifting. The costs are increasing, mainly due to Israel’s ongoing “campaign between the wars” (MABAM); while the potential economic benefits are dramatically declining due to Tehran’s economic crisis.

With Syria in economic turmoil because of the destructive impact of the civil war and recent US sanctions, these tensions can be exploited to induce Assad to limit Iran’s freedom of action on Syrian soil. Israel should open back channels to the regime and engage with the US over the need to make use of the opportunity. Given the supreme importance of the Iranian challenge, this is a necessary step – even if it requires a more nuanced view of the Syrian regime and the Russian role in Syria.

While Moscow maintains close consultations with Ankara and Tehran, the Russians, too, have their differences with both Turkey and Iran. The message to Assad and Putin should be clear and purposive: If and only if the regime will act to prevent Iran from penetrating the areas bordering Israel and Jordan and from transferring strategic weapons to Hizbullah – attitudes in Washington might begin to change. (An added benefit for the US may be the reduction of tensions with Russia in the Kurdish northeast.)

Assad is a bloody dictator. But since a strategic confrontation with Iran may be lying ahead, something that overshadows all other US and Israeli considerations, priority should be given to options that will deny Iran the capacity to use Syria as a base for bleeding Israel.

The Internal Power Game

A dramatic rift within the ruling family in Damascus plays a role in weakening Iran’s influence, a weakness that can be exploited, rather than lumping together all elements of the regime. For years (as long as Assad’s mother Anisa Makhluf was alive), Assad’s first cousin Rami Makhluf had a free hand enriching himself immensely in Syria. He controlled a business empire which according to some estimates controlled more than half of the Syrian economy. In 2011, when the revolt broke out (reflecting to some degree popular anger over Rami’s opulent displays of wealth and power) his assets were evaluated at $5 billion. He is under sanctions in both the US and the EU, but a complex web of overseas shell companies protects his interests.

With Anisa’s passing in 2016, however, a rift within the family gradually became visible, fed by Asma’s acute dislike of her husband’s cousin, and the growing realization that Makhluf’s voracious behavior had contributed to the hatred towards the regime. Asma apparently persuaded Bashar to strip Makhluf of some of his assets (due to his severe mismanagement of the regime’s energy policies) and to demand massive tax back payments, which led Rami to complain openly that he was being treated unfairly.

This estrangement within the family has acquired strategic overtones, generating an opportunity to broaden the gaps between Assad and the Iranians. Makhluf (hailing from a prominent Alawite clan) increasingly has been associated with the claim that the Alawites are a subset of the Sh’ia (which they are not). The Alawite or Nusayri faith includes elements that clearly put it outside the realm of Islam altogether. This fiction, however, enabled Makhluf to position himself as Iran’s key ally in Damascus and as an agent of Tehran’s long-term plans for the transformation of Syria into a Shi’a bastion.

The Russians, meanwhile, do not hide their dislike of Makhluf and his manners. A dispute has arisen over the pay for the services of Russian mercenaries. Attacks on the Syrian regime, in Russian media associated with Prigozhin (who owns the “Wagner” militias), turned out to be aimed essentially at Makhluf. Tensions between Russian- and Iranian-supported elements in the inner circle of power in Damascus could acquire growing significance if they are used effectively, by Israel and the US to broaden the gap between the two contending perspectives within the ruling family.

The Rising Cost (and Diminished Benefits) of the Iranian Connection

The tensions between the Syrian regime and its Iranian allies are rising against the background of a broader problem posed for Assad by the persistent Iranian presence on Syrian soil (complemented by Shi’a militias from Iraq and Afghanistan).

The benefits of the Iranian involvement in Syria are steadily diminishing, as the civil war becomes less intense, and as the ultimate outcome in the Idlib Province is determined more by Turkish-Russian understandings than military action by the IRGC and its allied militias, led by Hizbullah.

The flow of funds from Iran to Syria has also dwindled due to Iran’s extreme economic distress (caused by American sanctions compounded by the collapse of energy prices). It was Russia, rather than Iran, that undertook to support Assad’s war effort in Idlib, and Russia now sponsors the fragile arrangements reached with Turkey that have reduced the level of violence for the time being.

Meanwhile, the cost of the Iranian presence has been rising steadily, largely due to Israeli operations; the so-called “Campaign Between the Wars” (known by its Hebrew acronym, MABAM). IAF strikes have taken a toll in the lives, limbs and infrastructure of the IRGC and Iran’s proxies, and also have battered Syrian security and prestige. Over time, it has become clear to the regime that Iran’s ultimate purposes in Syria are starkly different, in terms of the confrontation with Israel, from those of Bashar and his family, the Alawites.

Assad is acutely aware that his military may have broken the rebels, but it is exhausted and would suffer decisive deficiencies if forced by Iranian interests to face the IDF in battle. Growing Syrian dependence on Iran, as demonstrated in the recent military agreement signed in Damascus at the level of defense ministers (and which theoretically commits Iran to continue aid to Assad), does not bode well for the regime’s long-term interests or even survival.

The Impact of the Libyan Situation

Tensions between Syria and Iran may also arise over Libya. In an ironic twist, the interests of Assad’s regime there, and those of its Russian backers, now coincide with those of France, the UAE, and Egypt (and therefore, also with those of Israel, Greece and Cyprus). The success of Erdogan’s military intervention, in support of the Fai’z Sarraj’s Government of National Accord (GNA), threatens the balance of power in the eastern Mediterranean. Erdogan sent Islamist Syrian rebel militias and the Turkish Sadat private militia to help the GNA. Assad, in response, has apparently sent regime loyalists to support the Libyan National Army (LNA) led by Haftar. Russian mercenaries and combat aircraft are also involved in the effort to stabilize the LNA front near Sirte and stop the eastward momentum of the GNA counterattack, and an Egyptian military intervention cannot be ruled out.

On the other hand, Iran is searching for common ground with Turkey, as indicated by Muhammad Jawad Zarif’s meeting in Ankara on June 15 with his Turkish counterpart Mevlut Cavusoglu. (This is the first major visit in Ankara since the COVID-19 outbreak began). Unlike Syria, Iran does not see with concern the military setbacks suffered by Haftar’s forces, which are supported by its regional rivals, the UAE and Egypt. This difference may become more pronounced over time.

The Role of Russia

Amidst these tensions and potential opportunities, the Russian role looms large. The support given by Russian aircraft to Assad’s regime’s brutal campaign of reconquest has angered many in the US and the West. More recently, Moscow has disrupted the UN efforts, backed by the US, to maintain humanitarian supply lines to rebel-held areas in northern Syria. Nevertheless, the overriding danger posed by Iran requires a more nuanced approach towards Putin’s policies in Syria.

Narrowing the present gap – indeed, chasm – between US and Russian policies in Syria could also assist in reducing the friction in northeastern Syria. There have already been incidents between US troops who are still active in the Kurdish areas and Russian forces operating in support of the regime. Given historical Russian sympathies towards Kurdish aspirations, and US ongoing support for the SDF, it is possible to envision a practical understanding in this sector of Syria. This, as long as the Kurds accept the nominal sovereignty of the regime, and US policy towards Assad (and hence, his Russian supporters) becomes more nuanced. Reaching an understanding with the Russians on the SDF will spare the US the accusation that it betrayed the Kurds once more.

The Russians are playing an extremely complex game in Syria (and in Libya), combining the use of force and multi-directional diplomacy, and taking pride in their ability to speak to all players. The overall structure of the “Astana Three,” namely Russia, Turkey and Iran, is still standing; and Putin conducts ongoing high-level conversations with Erdogan and Khamenei. Russia is also careful not to push Iran out of Syria altogether, and to avoid alienating Hizbullah, which Moscow absurdly describes as a force “fighting against terrorism.” All three desire to drive the US out of Syria.

However, beyond this common desire, and Putin’s cooperation in supporting Assad against Turkish-backed rebels, Putin’s purposes in Syria are quite different from those of Tehran and of Iran’s proxies. Putin’s first and ultimate priority is to ensure survival of the Assad regime.

Russia wants to see a consolidation of Assad’s rule over all or almost all of Syria – subject to the present practical understandings with Erdogan in the northwest. Russia wants some political reforms and stability. If the US would conditionally accept that the regime (if it changes course on Iran) is a fact of life, some US-Russian “modus vivendi” may be found, specifically in the Kurdish northeast. On the other hand, again, Iran wants to use Syria as part of a grander strategy of regional hegemony, linked to the agenda of ultimately destroying (and for the time being, deterring) Israel.

The Russians realize the high risks to the Assad regime, and to their investment in its survival, of letting Iran do as it pleases. Russia is also apprehensive, for its own reasons, of Islamist zealots of all colors. This is another source of tension that can be used in pursuit of Israeli (and American) goals against the Iranian regime and its ambitions.

Generally, it has been the policy of American administrations, including both the Obama and Trump administrations, to let Assad bleed and drag the Russians deep into the Syrian quagmire. While this is not necessarily against Israel’s interest, it is a secondary consideration when what is at stake is the primary effort against Iranian ambitions.

In this context, the Libyan drama provides an opportunity for understandings with Moscow that may have implications in Syria as well. With Turkish forces and Russian mercenaries directly involved in the fighting there, the scrapping of planned talks in Turkey by the Russian ministers of defense and foreign affairs, Shoygu and Lavrov, is an indication that the crisis between Russia and Turkey runs deep. Israel should work to persuade Washington to align with Egypt, France, the UAE, Greece and Israel (and Syria) rather than with Erdogan’s ambitions.

On Libya, and to some extent in Syria too, Iranian and Russian strategies in the region do not necessarily cohere. The Iranian regime is eager to win support in Ankara, which may also be complicit in circumventing US sanctions on Iran. Whereas Moscow’s interests clash with those of Erdogan on a broad range of issues.

Thus, while there are common Russian-Turkish-Iranian interests and frameworks for cooperation, a more nuanced US policy towards Syria could play on the differences among the three. This requires a possible change in the US stance, if Assad does take action to curb Iranian behavior (as elaborated in the next section). In short, to enhance Russian-Iranian tensions, the US (and Israel) need to reconsider their present polices towards Assad.

Possible Israeli Policy

Bashar Assad is no saint. His regime is complicit in the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Syrians. Assad has been an ally of Iran since 1979 and of major terrorist organizations for even longer. He and his father before him have been sworn enemies of Israel for two generations.

Therefore, none of the above should be read as advocacy for Assad’s rule; let alone for the notion (once held by some key players in Israel) that Assad should be enticed to make peace by Israeli withdrawal from the Golan Heights. On the contrary, it is Israel’s presence within range of Damascus, and Israel’s aggressive MABAM posture, which is generating a degree of tension between Assad and his erstwhile Iranian patrons. Both this presence and posture should be sustained.

At the same time, the indicators listed above should at least be examined as creating an opportunity (as yet, by no means a certainty) of exploiting the tensions between Damascus and Tehran; and should be done in a manner understood and perhaps complemented by Russian policy.

The far-reaching expectation that Iran can be pushed out altogether from Syria is not a realistic prospect at this stage. Nevertheless, two goals are possible and crucial:

- Ensuring that the limits outlined in the American-Russian-Jordanian agreement of 2017, which barred the presence of Iran and Iranian proxies in southern Syria, are strictly implemented.

- Establishment of firm Syrian restrictions on the transit of strategic goods through Syrian territory to Hizbullah in Lebanon. This use (and abuse) of Syrian territory is putting the regime on a collision course with Israel.

As already indicated, Israel’s main role can and should be in discreetly urging key American players to make use, in a specific and purposeful way, of the present tools of pressure on Assad. Down the road, some “carrots” could be added, such as IMF loans for reconstruction and basic human needs. This must also involve a reconsideration of the present too passive and even supportive US responses to Turkish adventurism in the region, and specifically in Libya.

American sanctions are now in force, reflecting an understandable American response to horrifying revelations about repression, torture, and murder in Syrian jails. But if properly tied to realistic goals, the sanctions can be used as a lever to bring about specific changes in regime behavior; specifically, making it less obedient to Iran. The profitless pursuit of Assad’s overthrow could lead to the loss of an important opportunity.

From an Israeli perspective, it is also important to link the Syrian and Libyan cases. By mapping a common interest with Syria in Libya, the gap between Assad and the Iranians can be widened. Iran’s support for the GNA, openly expressed by Javad Zarif in Ankara (June 17), puts Tehran on this specific issue on the other side of the divide from Assad’s position. Since any direct involvement in Libya is out of the question, the most useful role Israel can play will be in focusing attention in Washington, among key administration officials and in Congress, on the full implications of the developments in Libya and the need to oppose Erdogan’s ambitions and Iran’s meddling.

The goals should be realistic. Neither Syria nor Russia will break openly and fully with Iran, certainly not at this stage. Both Damascus and Moscow need to keep their channels to Tehran open. For Assad, there can be no repeat of Sadat’s dramatic divorce with the Soviets after 1973. However, with a well-designed mix of pressures and inducements, both he and Putin may be persuaded not to take unnecessarily active risks in support of Iranian ambitions to use Syria as a base of attack against Israel. Specifically, they can be persuaded to ensure that Syrian soil is not used for provocations aimed at the Golan, or at penetration into Jordan (along the lines of the tripartite U.S.-Russian-Jordanian MoU of 2017). Nor should Syrian territory be used to transfer of sensitive items to Hizbullah. However, Israeli-Russian dialogue on these issues must be preceded by US-Israel coordination; and perhaps followed by another US-Russian-Israeli tripartite discussion at the level of national security advisers.

This would require (through Congressional action) a more purposeful application of the current sanctions on Syria. For example, wavers could enable Russia to invest in Syrian sectors such as agriculture and pharmaceutics which lie outside the present system of sanctions.

Assad will not be brought down soon, nor will he sever his link with Iran altogether. Neither will Putin. But if the sanctions are used wisely and selectively rather than as a blunt tool in a vain attempt to topple the regime, Assad and Putin may be willing to discreetly curtail Iran’s use of Syrian territory for purposes that do not serve Syrian and Russian interests. At this point in time, Assad and Putin have not yet been given sufficient incentives to distance themselves from Tehran.

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.